Have you ever watched a family adapt to life in a new country? Maybe you’ve seen their children pick up the local language faster than their parents. Or noticed how holiday traditions start mixing together in unexpected ways. This everyday phenomenon has a name: cultural assimilation.

Whether we realize it or not, assimilation shapes nearly every modern society on Earth. It touches everything from the food we eat to the values we hold dear. It opens doors to incredible opportunities while challenging our sense of identity.

What Exactly Is Cultural Assimilation?

Cultural assimilation refers to the process where individuals or groups gradually adopt the practices, values, and beliefs of another culture. This typically means taking on the dominant culture in their society.

Think of it as a gradual blending. The minority culture becomes absorbed into the mainstream. Sometimes the original cultural distinctions fade away entirely.

Key terms to understand:

- Assimilation: Fully adopting the dominant culture, often losing original cultural identity

- Acculturation: Cultural exchange where both groups influence and change each other

- Integration: Participating in broader society while maintaining distinct cultural identity

- Multiculturalism: Multiple cultures coexisting and being celebrated within one society

The sociologist Milton Gordon identified seven stages of assimilation. These start with adopting language and customs. They eventually lead to complete structural assimilation, where people enter all aspects of social life in the new culture.

Three Main Drivers of Cultural Assimilation

Understanding why assimilation happens helps us grasp its complexity. Three primary forces push cultural assimilation forward.

Immigration as a Driver:

When people move to a new country seeking better opportunities, they feel pressure to adapt. They want jobs, friends, and successful lives. This creates natural motivation to learn local languages and understand social customs.

European immigrants to America during the 19th and 20th centuries followed this pattern. German, Irish, and Italian communities gradually blended into American society over generations.

Colonization as a Driver:

Colonization represents a much darker form of assimilation. Colonial powers forced local populations to abandon their cultures. They imposed languages, religions, legal systems, and social structures—often through violence.

Examples include:

- Spanish colonization of Latin America

- British control of India

- French colonization of Algeria

- European settlement of Australia

Globalization as a Driver:

Today, assimilation increasingly happens through globalization. American and European values spread through movies, music, and social media.

Young people worldwide grow up watching the same shows. They wear similar fashion and adopt comparable lifestyle. This creates subtle pressure to conform to a globalized culture.

The Three Theoretical Models of Assimilation

Sociologists developed different frameworks to understand how assimilation works. Each model captures different aspects of this complex process.

The Classic “Melting Pot” Model:

This traditional model views assimilation as a linear process. Each generation becomes more similar to the dominant culture. Eventually, everyone blends into a unified culture.

Criticisms of this model:

- Assumes all groups follow the same path

- Treats white Protestant culture as the standard

- Ignores persistent discrimination against some groups

The Racial/Ethnic Disadvantage Model:

This framework recognizes that assimilation isn’t equally available to everyone. Race, ethnicity, and religion profoundly affect experiences.

Some immigrants assimilate easily because they look similar to the dominant group. Others face persistent racism regardless of how well they adopt cultural practices.

The Segmented Assimilation Model:

This theory suggests different immigrant groups follow different pathways. The direction depends on socioeconomic status, settlement location, and community support.

Three possible pathways:

- Classic upward mobility into mainstream society

- Downward assimilation into disadvantaged segments

- Economic success while maintaining cultural traditions

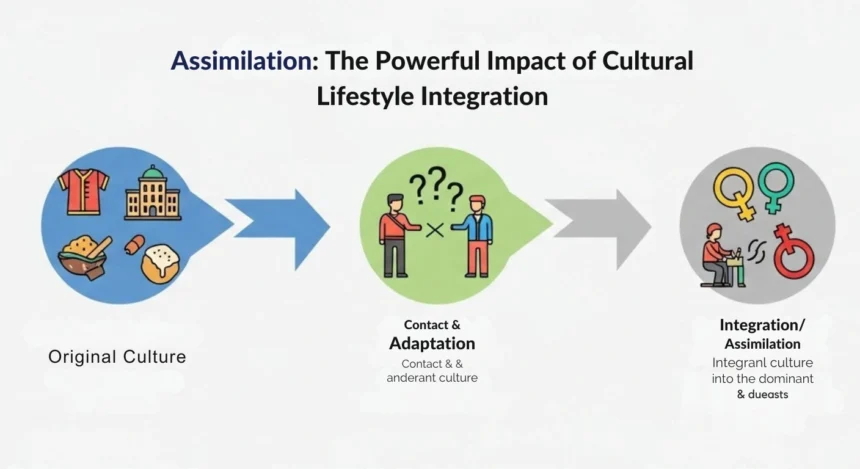

The Journey of Assimilation Five Key Stages

Initial Contact:

When cultures first meet, differences feel overwhelming. People encounter unfamiliar greetings, foods, and social rules. This stage brings heightened awareness of cultural differences and often confusion.

Conflict and Tension:

Differences in values and traditions lead to misunderstandings. Immigrants may feel defensive about their heritage. Host society members might feel threatened by newcomers. Working through these tensions is painful but essential.

Accommodation:

People start adjusting while keeping important heritage pieces. A family might learn the local language for work but speak their native language at home. They celebrate both traditional and new holidays. It’s a constant balancing act.

Integration and Adaptation:

Boundaries between cultures start to blur. People feel comfortable navigating their new environment. They understand unspoken rules and participate fully in community life. Research shows longer residence correlates with higher life satisfaction.

Full Assimilation:

Individuals become essentially indistinguishable from the dominant culture. Original practices are preserved only for special occasions. Not everyone reaches this stage and many argue complete assimilation isn’t necessary or desirable.

20 Signs of Cultural Assimilation in Everyday Life

Assimilation shows up in countless small ways. Here are specific behaviors that indicate it’s taking place:

Language Changes:

- Using dominant language as primary communication

- Reducing accent or adopting local speech patterns

- Using local slang and expressions

Identity Shifts:

- Changing names to sound more “local”

- Feeling embarrassed about cultural background

- Distancing from ethnic community

Lifestyle Adaptations:

- Adopting dominant culture’s fashion

- Abandoning traditional clothing

- Substituting traditional foods for local cuisine

Social Changes:

- Prioritizing friendships with dominant culture members

- Adopting local dating and relationship norms

- Participating in mainstream holidays and celebrations

Value Adjustments:

- Internalizing dominant culture’s beliefs

- Conforming to local views on gender roles

- Adopting local parenting styles

| Factor | Impact |

|---|---|

| Language Proficiency | English proficiency can boost income by over 33% |

| Age at Arrival | Those arriving before age 9 develop native-like language skills |

| Societal Attitudes | Welcoming communities accelerate integration |

| Education Access | Schools serve as primary socializing institutions |

| Economic Opportunities | Job availability strongly influences motivation to integrate |

| Community Size | Large ethnic communities may slow assimilation |

| Cultural Distance | Similar cultures assimilate faster |

| Family Dynamics | Intermarriage accelerates assimilation across generations |

The Benefits of Cultural Assimilation

Economic Opportunities:

Assimilation brings clear economic advantages. Research from Stanford University found that culturally assimilated immigrants saw real gains for their children.

Economic benefits include:

- Higher wages and employment rates

- More years of completed schooling

- Greater access to job opportunities

- Ability to start businesses and create jobs

Learning the dominant language well can boost income by over 33 percent.

Stronger Social Connections:

Assimilation leads to deeper community bonds. When people share cultural reference points, forming friendships becomes easier. They know the same songs, understand the same jokes, and follow the same sports teams.

Studies found a positive correlation between cultural assimilation and life satisfaction. People who identified with the host culture reported higher overall well-being.

Reduced Social Friction:

Shared cultural ground means less conflict and misunderstanding. Children of immigrants who integrate well are received more positively by peers. Shared values create smoother interactions in schools and workplaces.

Better Access to Services:

Assimilation opens doors to education, healthcare, and legal systems. Understanding how institutions work makes a tremendous practical difference. People know whom to ask for help and can communicate effectively with officials.

The Challenges and Costs of Assimilation

Loss of Cultural Identity:

Languages spoken for generations can disappear within one generation. Traditional recipes, folk songs, and family rituals may fade away. This loss feels deeply painful, especially for older generations.

What gets lost:

- Native languages and dialects

- Traditional foods and recipes

- Religious and spiritual practices

- Family customs and rituals

- Traditional arts and crafts

Psychological Stress:

The pressure to assimilate creates mental health challenges. People feel caught between two worlds—not fitting into either culture.

Second-generation immigrants often experience this acutely. They navigate family expectations to maintain traditions while facing peer pressure to conform.

The Immigrant Paradox:

Here’s something surprising. Recent immigrants often have better health outcomes than both native-born citizens and fully assimilated immigrants. As immigrants assimilate over time, their health often gets worse, not better.

This suggests maintaining cultural connections may be protective. Strong community bonds and traditional practices buffer against stress.

Discrimination Despite Assimilation:

Assimilation doesn’t guarantee acceptance. Racial and ethnic minorities may face prejudice regardless of how well they adopt the dominant culture.

Asian Americans illustrate this complexity. Despite being called a “model minority,” they face the “perpetual foreigner” stereotype. The COVID-19 pandemic triggered anti-Asian violence despite generations of successful integration.

Forced Assimilation Trauma:

History contains many dark examples of forced assimilation. Indigenous peoples in the US, Canada, and Australia faced brutal policies designed to erase their cultures.

Forced assimilation methods included:

- Removing children from families

- Banning native languages

- Forbidding traditional ceremonies

- Forcing religious conversion

- Destroying cultural artifacts

These practices caused generational trauma that communities still heal from today.

FAQs

What is the difference between assimilation and acculturation?

Assimilation means fully adopting the dominant culture, often abandoning original identity. Acculturation is broader it describes cultural change when different groups interact. Both groups may change, and neither culture is necessarily abandoned.

Is cultural assimilation good or bad?

Neither universally good nor bad. Voluntary assimilation provides economic opportunities and social connections. Forced assimilation causes tremendous harm. The key factors are whether it’s freely chosen and whether people have support.

How long does cultural assimilation take?

About half the cultural gap closes after 20 years of residence. Full assimilation often takes multiple generations. Children and grandchildren typically show more cultural similarity to host society than parents.

Can you assimilate while keeping your original culture?

Yes. Many people successfully integrate participating in society while maintaining heritage. This “bicultural” approach is increasingly seen as preferable. Complete abandonment of original culture isn’t necessary.

What is the “immigrant paradox”?

Recent immigrants often have better health than both native-born citizens and assimilated immigrants. Despite fewer resources, new immigrants show lower mental illness rates and stronger family bonds. These advantages often disappear with assimilation.

What’s the difference between melting pot and cultural mosaic?

The “melting pot” (United States) envisions all cultures blending into one unified culture. The “cultural mosaic” (Canada) encourages maintaining distinct identities while participating in national life. Melting pot emphasizes similarity; mosaic celebrates diversity.

Final Thoughts

Cultural assimilation remains one of the most powerful forces shaping our world today. It offers genuine benefits economic mobility, social belonging, and reduced conflict. But it also carries real costs in terms of lost heritage and identity.

The healthiest approach seems to lie somewhere in the middle. Biculturalism allows people to participate fully in society while preserving meaningful connections to their roots. When individuals have genuine choice about their cultural identity, outcomes improve for everyone.

As our world grows more interconnected, these questions will only become more important. The challenge is creating communities where people can contribute fully while being valued for who they are heritage and all. That’s worth striving for.